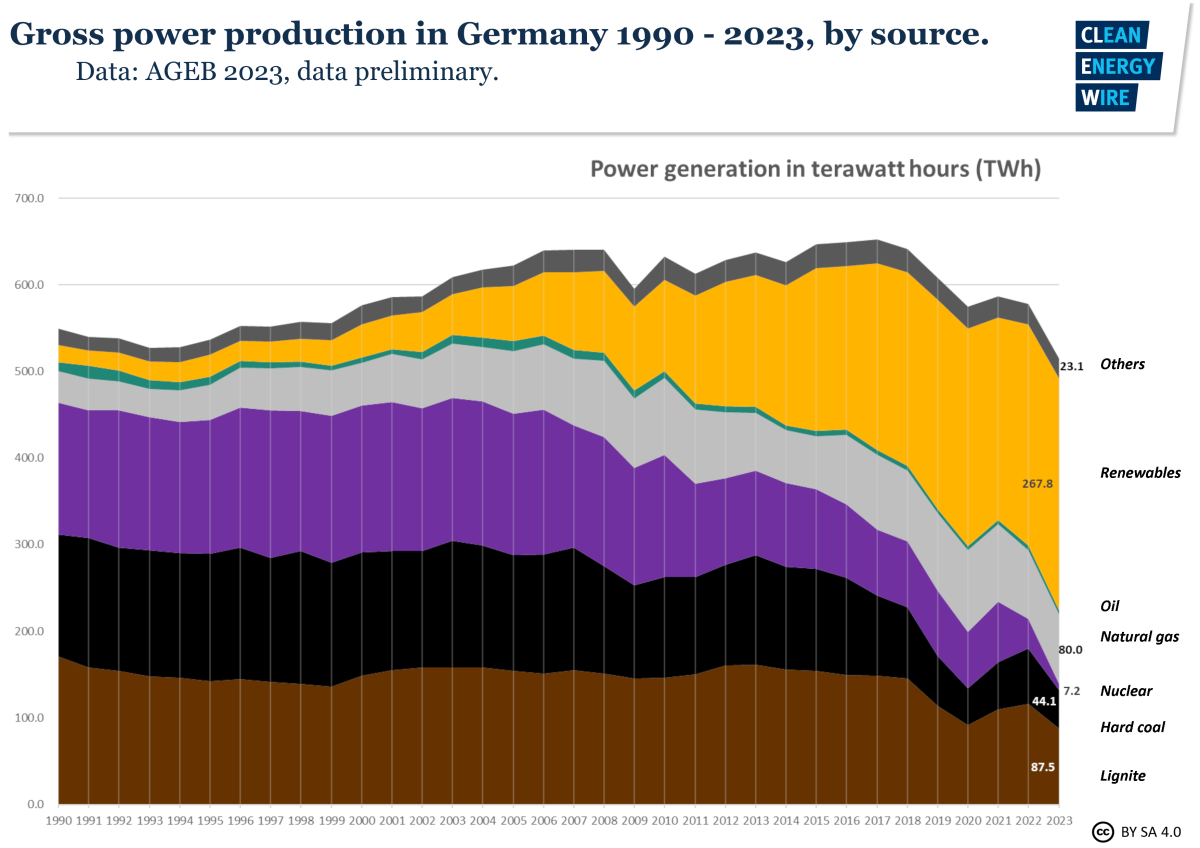

I love this graph. It reveals that two important trends have both accelerated over this last year. Electricity demand in Germany has fallen more quickly than ever and renewable forms of electricity have increased significantly, which, taken together, has meant that coal, lignite, gas and nuclear power have simultaneously fallen. This proves the success of the German ‘Energiewende’ policy.

The graph shows how use of the most polluting ways of generating electricity (lignite, coal, gas, oil and nuclear) collectively peaked in 2003, plateaued until 2006 and then, first slowly, then increasingly quickly, declined. This was made possible between 2003 and 2017 by the increasing deployment of renewables, notably wind and solar. Overall demand peaked in 2017, and has since fallen significantly, which coupled with the continued increase in renewables, has meant increasingly rapid falls in the more polluting technologies. Very good news in many ways: falling carbon emissions, declining local air pollution, and wider economic and social gains from new jobs, health benefits, money saved on fuel imports etc.

The 2020 to 2022 period saw some extraordinary challenges. First Covid, which reduced demand, then the post-Covid bounce in demand overlapped with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine which interrupted gas supply, coupled with a severe drought that meant that most of Europe’s hydro-electric facilities were only partially operating, which had the knock-on effect of meaning French nuclear power stations had insufficient water to operate and had to shut down. All these factors were behind the slight increase in lignite, coal and nuclear that occurred around 2021 and I blogged about last year.

I posted a blog in 2014 ‘The Energiewende: Success or Failure’. I think we can now say, yes, it has been a success. Germany is moving toward 100% renewable energy generation.

More than a dozen countries already get all, or very nearly all, their electricity from renewables: New Zealand, Iceland, Costa Rica, Bhutan, Uruguay, Albania, Paraguay, Kyrgyzstan and a few others. None have huge populations or a lot of industry, and all have very good renewable energy resources, mostly hydro. Why the German Energiewende is significant is that it was the first populous, heavily industrialized country to make this a specified policy objective. Now most countries are moving in this general direction. The Ember website has data for nearly all countries. Many countries in the global south are still witnessing increases in electricity demand, and so globally coal use increased slightly last year. However it looks increasingly likely that global coal use will peak this year, or maybe next, then plateau for a couple of years before beginning an increasingly rapid decline. China’s massive recent investments in renewables are a harbinger of this.

To combat the global climate and ecological crisis humanity needs to change in many ways. One of the most obvious, and important, is to stop burning fossil fuels. Changing how we generate electricity is a big part of this, and the falling demand and increasing use of renewables that this graph shows for Germany gives inspiration for other countries to follow. It makes economic and ecological sense. Every year this transition becomes easier as renewable energy gets better and cheaper, energy storage technologies improve and grids are interconnected. This is one area where humanity is (albeit falteringly, chaotically and despite powerful vested interests) moving in the right direction.